Anna’s sailplan is tall, simple and fast.

Sailboats are just that: Boats that move because they have sails. So while we spend lots of our time figuring how out how slick mechanical systems operate winches and cool the air below, at the end of the day a boat like our new 66-footer Anna, just finishing up at Lyman Morse Boatbuilding, is a sailboat: Her central role is to provide her owners and crew the delightful experience of cajoling the wind into pushing or pulling all through the water — in more or less the direction the crew wants to go.

Since Anna’s chief propulsive force is the wind, capturing that force is the job of the rig and sail plan.Getting this plan right, for a boat like Anna is not all cold engineering. It’s as much a psychological choice, as a technical one. (Click here for Anna’s full high-rez sailplan.)

Our job is to match this sail plan to the style of sailing the owners want to embrace. Anna’s owners set their sights on easy, low-stress daysailing. While they’ll sail with a couple of professional crew, they wanted things to remain low-key. The gear should be all about easy short-handed sailing. But (there’s always a “but!”) the owners wanted to show Anna’s speed off at Spirit of Tradition regattas. We her designers set the bar high. When Anna races, we wanted her to win!

Fortunately, nowadays you can have both simple and fast. Our first decision was to stay away from big, overlapping genoas. In rule-beater boats of the 1930’s, a big 150-percent genoa jib added unmeasured and unrated area. Performance was higher than for a smaller working jib, but only slightly. And the downsides are huge. Tacking a big headsail is a bear — dragging a massive sail around the shrouds and spreaders. Sheeting angles are wider, so upwind sailing slots are sloppier. Improving sheeting angles requires moving shrouds inboard, which drives rigging loads and mast weight and windage up and up and up. Basically, overlapping jibs are a mistake. That’s why we haven’t designed a boat with one for more than a decade.

We find we can engineer enough sail power with a basic main and working jib pair, that will drive any boat well in all but the lightest winds. We look to reefing the main to keep things under control when the wind pipes up.

A Classic Main

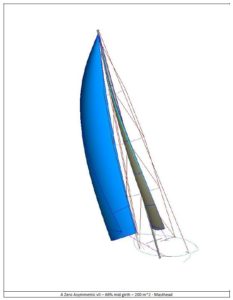

Anna’s big reacher modeled going to windward, via North Sails Design Team.

Which brings us to the mainsail. Today’s roller-furling booms work well for keeping larger mains manageable by smaller crews. Plus they give away little in performance, compared to their race-boat relatives. Push a button, and Anna’s large main sail will roll away as the breeze grows and will shift the center of effort forward to keep the helm well-balanced. While we’ve found great performance and value in square-headed mainsails in recent years—lower drag, noticeably less heeling force per unit of forward drive, and easier trimming— Anna’s mission of simple sailing is better-suited to a conventional, triangular Marconi rig, with a permanent backstay with a hydraulic adjuster. That’s how we bend the mast to shape the draft on this fully-battened rollaway main.

Even so, Anna’s mainsail will be mainly about simplicity.

How’s the Headsail Working?

Anna will feature two jibs: A self-tacking daysailing headsail of about 90% LP, and a “race” jib, that’s basically just a fast working jib of about 106 percent LP. Both will furl on the hydraulic roller, so management will be easy for either putting the boat away after a two-hour cocktail cruise or rounding the windward mark and setting the downwind kite.

In daysail mode, tacking will merely mean putting the helm over—the boomless headsail on a curved track will slide from port to starboard. Nothing could be simpler.

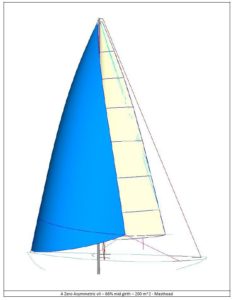

Large off the wind sails will give power to Anna, via North Sails Design Group

When sheets are eased, Anna’s crew will have a couple of choices for lighter sails, though both will easily manageable, via the folks over at North Sails. A Code Zero headsail that is the modern incarnation of an old-fashioned “reacher:” A big high-clewed powerful sail for anything from close-reaching in the light going, to full-on downwind use when cruising or delivering the boat. In really light air, this sail will make the difference between drifting and sailing. It will be set on a continuous-line furler with a torque rope, so putting it away is just a matter of pulling a string. Also a poleless asymmetrical spinnaker will get Anna downwind in a hurry. It will be the choice when racing. A spinnaker sock will keep that sail under control, although 3,000 square feet of any sail will always be a challenge in a breeze.

We talked quite a bit with the designers North Sails about Anna’s off-wind inventory. We walked through a roller-furling top-down system for a spinnaker, but didn’t like the compromises in sail shape. It appeared a flatter, smaller — and slower sail — would have been required.

Remember, we are looking for winning performance when Anna races.

Some Smart Sticks

Spars are key to sail performance. And that’s all about getting weight out of the rig. Yachts must have the stability and power to stand up to their sail plan. Our spar makers focused on lightweight and durable materials: Carbon in the extrusions and standing rigging made sense, but a complex and heavy traveler on the cabin-top did not. That’s extra weight and cost for limited additional control. We also left out carbon stays for the jib furler. That kind of techno-exotica didn’t fit the simple mission of this boat. In all, we expect Anna to be a wholesome, relaxed and fun dayboat/cruiser, that will also flash surprising speed if well sailed on the racecourse.

We can’t wait to get out on her and see where her sails take us.