A Rock. And a Hard Place: Lessons Learned Going Aground in Hoi An

Here’s what happened: It was a normal Maine summer day. Half work, half play. Paul and I were out of the office, moving Hoi An from her mooring in Blue Hill to Camden. Her owners had kindly loaned the yacht to us for racing in the Camden Classics Cup to act as sponsor’s boat. The morning fog had cleared and a cracking breeze had come up; we were closing Camden fast, beam-reaching at over eight knots.

I was navigating using the older, below-decks-mounted chartplotter occasionally, confirming with dead-reckoning, sighting islands, buoys, and landmarks. These weren’t my home-waters, but I had raced them frequently over a couple of decades. And although I was headed east-to-west , opposite the typical race-course, I felt comfortable with the navigation.

Suddenly the picture of the position I was getting on deck didn’t quite jibe with what I expected. I jumped below to check on the plotter, and — WHAM! The day went bad.

I had just sailed a 50-footer brains-first into Maine granite.

After checking that all aboard were okay, we sorted things out, backed off the rock and … evaluated. We had water coming in, but rig and keel seemed intact. The electric pump wasn’t keeping up. Fortunately I knew where the manual pump was located, and the handle was in place. Lucky break there. Paul fired the diesel immediately and negotiated the yacht away from danger, and we continued on towards closest safety motor-sailing toward Camden. With me pumping and Paul sailing, we scooted across West Penobscot Bay; and an hour later we were in the slings of the Travelift at Lyman Morse’s Wayfarer Marine. That was a wonderful feeling of relief. The vessel was safe; now the process of making her whole again could begin.

Lessons Learned

This was a very rude awakening for me. I had always thought of myself as a careful and prudent navigator. But prudence doesn’t get you piled up on a rock. I’ve looked deep into my thoughts and actions to get at how I ended up there.

- Complacency. I had sailed these waters many times. We had a GPS so our location on earth was never in doubt. How careful did we need to be? Lots more careful, it turns out. While navigation by sight and paper chart had always worked for me in the past on my own boat with minimal nav aids, and while my racing career has often put me in the position of dedicated navigator, the combination of GPS and inattention is dangerous. When navigating by chart and sight with no instruments, I was much more vigilant than I had been that day. When navigating full-time I was much more attentive to the GPS. That day, I fell into the slot between those two styles of navigating.

- Short-handed. With only the two of us aboard, we didn’t take the time to focus on the navigation to the extent every sailor should.

Equipment. Equipment is not to blame, inattention is. But, there are some valuable lessons here: First, GPS equipment only works when you look at it. Hoi An’s plotter is below at the chart table. This works great when fully-crewed—when we race her with eight aboard, I spend almost all my time staring at that screen—no sunscreen required! But that day, I was reluctant to be below on a good sailing day, so I was hopping down every 15 minutes or so for a quick look, then referencing landmarks while on deck. This was not enough. Second, the plotter was older, so its display was different from government charts. I misread the rock as an islet exposed at all tides—in fact it was submerged at high water. I mis-identified a small island as the rock we needed to avoid, and thus thought we were okay even while we drove toward disaster. Know your equipment and its faults, and act accordingly.

Equipment. Equipment is not to blame, inattention is. But, there are some valuable lessons here: First, GPS equipment only works when you look at it. Hoi An’s plotter is below at the chart table. This works great when fully-crewed—when we race her with eight aboard, I spend almost all my time staring at that screen—no sunscreen required! But that day, I was reluctant to be below on a good sailing day, so I was hopping down every 15 minutes or so for a quick look, then referencing landmarks while on deck. This was not enough. Second, the plotter was older, so its display was different from government charts. I misread the rock as an islet exposed at all tides—in fact it was submerged at high water. I mis-identified a small island as the rock we needed to avoid, and thus thought we were okay even while we drove toward disaster. Know your equipment and its faults, and act accordingly.- Preparation. We hadn’t set off that morning with the idea that we’d be in distress that afternoon. We were lucky that we knew the boat well. Locate the emergency equipment. Know that you can use it. A manual pump is no good without its handle!

- Danger. A hard grounding is no joke—people can get hurt, badly. I didn’t fully appreciate that until now. We were lucky—I suffered a broken rib, from hitting the galley counter (I think) when we went from full speed to full stop. The rest of the crew suffered only bruises. It would have been a very different scenario if we had hit seconds earlier, when I was getting ready to descend the companionway—I would have been flung forward and down with great force.

Other Hard Lessons: Built to last.

Even today with all the engineering software at designers’ disposal, it’s impossible to know exactly how a structure will fail without actually seeing it stressed to breaking. Heart-breaking as it was, Hoi An’s grounding was an opportunity to study and learn, so our structural designs in future boats can be improved. As it turned out, we were pleased to see how well she stood up to a hard grounding at close to max speed—while the hull was breached, the water inflow was quite limited—and more importantly, the damage was extremely localized. Basic structure remained intact; the boat was solid and sailable, although holed. We could have kept sailing and pumping for a few days, if need be.

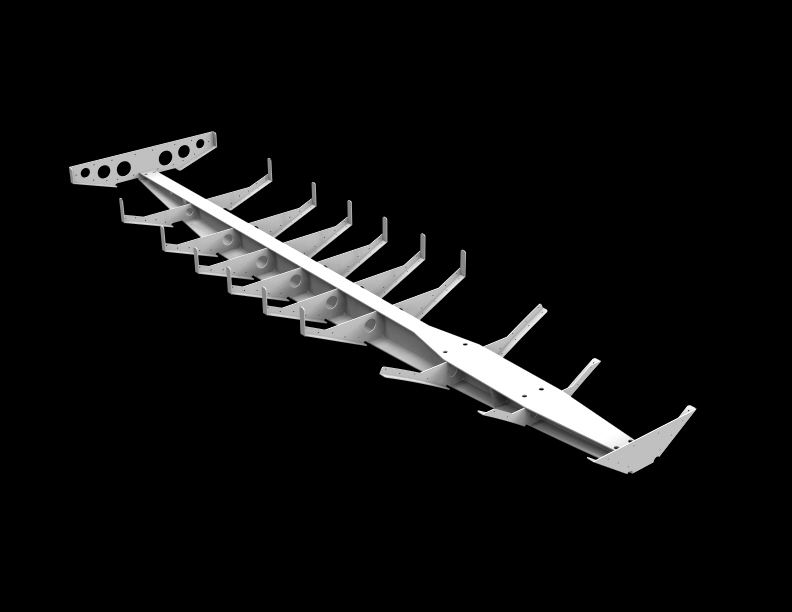

Hoi An’s structure is designed around a central keel frame—a bronze fabrication that ties together the keel bolts, mast step, and hull structure and contributes tremendous longitudinal strength and stiffness The impact pulled the forward end of the keel fin down, splitting the planking on each side of the fin, and pushed the aft end up against the keel frame, slightly cracking the planking at the back end. But the keel frame absorbed the lion’s share of the impact, distributing it evenly through the yacht’s wood structure. In many yachts, an impact like this would have broken the interior loose from the hull, causing tremendous repair costs.

With Hoi An, the hull planking and centerline wood structure required repair, but damage elsewhere was non-existent.

What Gets Fixed.

Another lesson was to see just how repairable a cold-molded wood boat is. The repair is exactly like the original build process—cut away the damaged wood, step back the layers of hull planking, cut scarfs where new wood is bonded in, and rebuild the four-layer hull planking. Unlike a composite boat, there’s no concern about secondary bonds to old, contaminated FRP surfaces. While the job was extensive, expensive, and time-consuming, the disruption to the yacht was minimal and the repair is every bit as good as new.

Hoi An’s in winter storage now, but we know she’s ready to get back out there on the water.

Equipment. Equipment is not to blame, inattention is. But, there are some valuable lessons here: First, GPS equipment only works when you look at it. Hoi An’s plotter is below at the chart table. This works great when fully-crewed—when we race her with eight aboard, I spend almost all my time staring at that screen—no sunscreen required! But that day, I was reluctant to be below on a good sailing day, so I was hopping down every 15 minutes or so for a quick look, then referencing landmarks while on deck. This was not enough. Second, the plotter was older, so its display was different from government charts. I misread the rock as an islet exposed at all tides—in fact it was submerged at high water. I mis-identified a small island as the rock we needed to avoid, and thus thought we were okay even while we drove toward disaster. Know your equipment and its faults, and act accordingly.

Equipment. Equipment is not to blame, inattention is. But, there are some valuable lessons here: First, GPS equipment only works when you look at it. Hoi An’s plotter is below at the chart table. This works great when fully-crewed—when we race her with eight aboard, I spend almost all my time staring at that screen—no sunscreen required! But that day, I was reluctant to be below on a good sailing day, so I was hopping down every 15 minutes or so for a quick look, then referencing landmarks while on deck. This was not enough. Second, the plotter was older, so its display was different from government charts. I misread the rock as an islet exposed at all tides—in fact it was submerged at high water. I mis-identified a small island as the rock we needed to avoid, and thus thought we were okay even while we drove toward disaster. Know your equipment and its faults, and act accordingly.