Retro Golden Globe One-Design Racer Gets Lost In Design Time.

Hey, Don McIntyre! You’re the organizer of the Golden Globe 2018 single-handed round-the-world race. You know, the one where anybody can grab a select list of old fiberglass boats and go around the world non-stop, with not much more than a sextant.

Is there a rule we missed that says the new one-design for your race has to be a slow boat to China and back?

It’s not like we’re not big fans of the coming Golden Globe Race 2018. We flat out love how your GGR will send off a mixed fleet of about 30 professional and amateur sailors. Each of whom will race around the globe alone in wholesome, full-keel, reasonably-priced boats. We’ve spoken to you directly about how your race brilliantly tells a fresh sailing story, beyond the tired tale of esoteric vessels and rarefied crews blasting around the globe in Volvo and Vendee Globe races: With some skill — and luck — anybody can ride your race’s retro vibe to sailing glory. It’s a goal for any adventurer. The GGR reminds us all why we go to sea.

But as designers who get paid to update classic naval idioms, it‘s our professional duty to ask in public — with love and kindness — why, oh why, would anybody enter your Golden Globe race in the newly created one-design Joshua class, that was announced for the running of the next race in 2022?

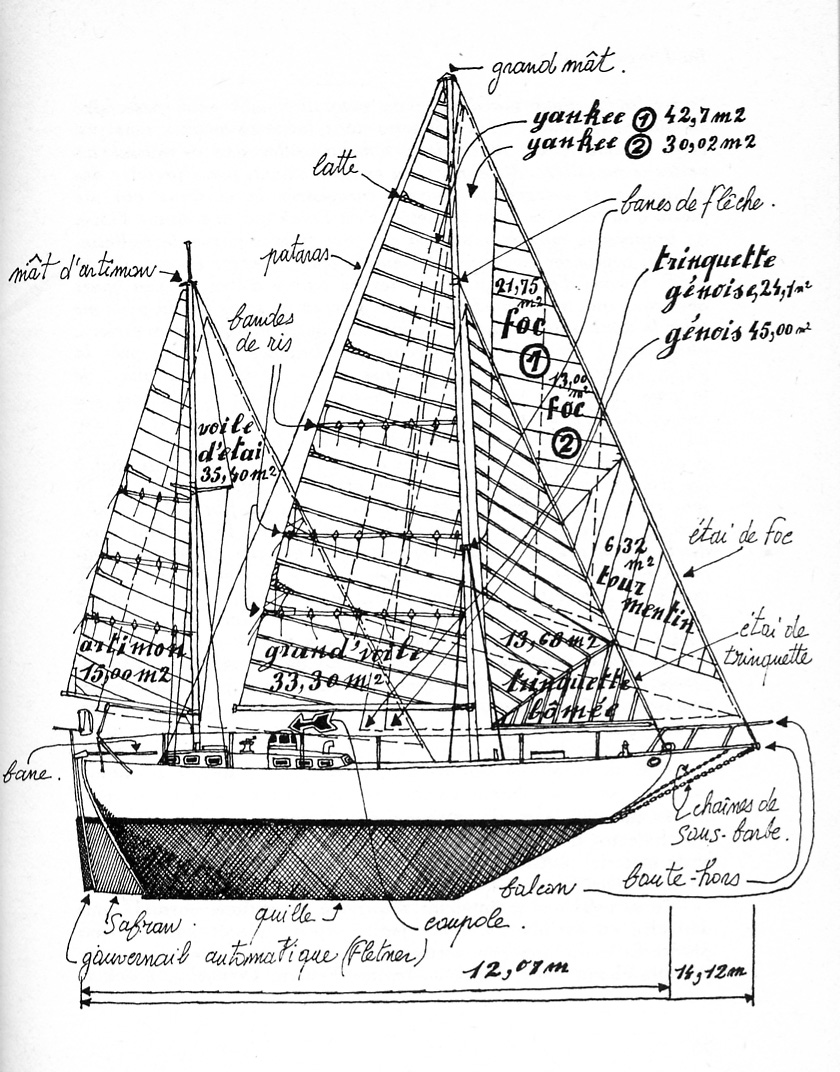

Because, at least according to the images and data we’re seeing, this design is not Bernard Moitisser’s Joshua. That boat already exists. Several of these Jean Knocker-designed steel ketches are still afloat; many that come up for sale from time to time. The “Joshua GGOD” we are seeing, on the other hand, is an entirely new design for new customers in the 21st century.

In that modern context, this Joshua is merely a collection of old ideas kept around for old ideas’ sake. And that’s a terrible story to ask any boat to tell.

An ancient “Joshua,” indeed.

Bernard Moitessier’s original Joshua was — and is — an old boat. Even though the Golden Globe took place in 1968, her design was based on the famous Colin Archer lifeboat genre, which rests on design theory from the last century. And even though that’s the result of yet more centuries of development in the tough North Sea, the technological choices available to builders today dramatically changes how boats like Archer’s should work.

We designers have heard all the arguments for refusing to listen those new stories in boatbuilding: Double-ended hulls can be tough and durable, you might say. Sure, these boats may be sturdy and welded-steel construction is indeed rugged. But so are modern materials like fiberglass, wood and epoxy. More importantly, in the last hundred years, we have learned that a light, buoyant boat is safer in moderate-size waves. The light boat rides them like a cork. She is not overwhelmed like a heavy boat. And in the monster stuff in the big Southern Ocean that the lighter cork-like boat will slide away from the impact of a breaking sea. The heavy boat will try to resist that wave, like a half-tide rock stuck in the mud. Moitessier talked often about how the green water hitting his Joshua was like concrete. That’s why.

Maneuverability over mass is safety in a seaway. The ability to maintain control and keep the boat running down a wave, rather than sideways in a trough, is the accepted way to navigate exposed open water.

But Joshua’s solid design will “look after her crew,” you say. But ah, that’s the real killer misconception. Today’s Joshua one-design features mid-century ideas in rigging and sail-handling that guarantee her crew will be stuck on deck struggling with archaic systems. The Golden Globe 2018 currently allows for modern safety equipment like LED lights and self-tailing winches. For boats of this weight, modern sail handling gear is absolutely mandatory. Because the effort to sail any boat is directly proportional to the weight of that boat. We estimate today’s Joshua class will be 60 percent heavier than a lighter, modern vessel.

This Joshua will require at minimum 60 percent more labor for every tack, gybe, and sail set than a boat of smarter more reasonable technology. We can’t imagine how tiring this boat will be to sail.

Dangerously slow

If we haven’t convinced you yet, let’s talk performance. Robin Knox-Johnston, the only one of nine competitors to complete the Golden Globe course on time, made it around in 313 days. If anybody wants that experience, enter the current race. Today’s retread boats will probably finish in that time frame.

But for a modern-day build, Joshua’s performance numbers are irrational: The sail area-to-displacement ratio is about 16.7 — or just above the “motorsailer” threshold! Most cruisers have SA/D ratios from 17 to 22. Her displacement-to-length ratio is a whopping 394, which is amongst some of the heaviest boats drawn. Ever. A more typical D/L ratio falls into a range around 120-300. That means, today’s Joshua will spend much of her sailing life at speeds well under her theoretical hull speed of 7.8 knots. Historically, we know most cruisers from fifty or sixty years ago were lucky to make an average of 100 miles per day, or four knots/hour.

To be honest, we doubt this boat will ever overhaul a well-sailed Rustler 36 or Hinckley Pilot 35. Those boats can get moving with good sailors and conditions.

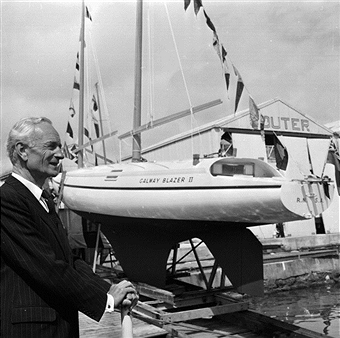

How about a boat for Bill King?

How slow is today’s Joshua? Let’s compare her to what we might expect from a modern 40-foot ‘round-the-world cruiser that a living designer — ok, us — might draw. We would christen our world racer the Galway Blazer III, after Bill King’s fascinating and innovative ultralight 42-footer that also started as part of the original Golden Globe Race in 1968. It’s not well known, but King completed his Golden Globe lap of the globe, but only after five years of trying. And a series of mostly unrecorded capsizes, structural damages, and health problems. King crossed back into Plymouth, unannounced, in 1972. It was a seamanship achievement equal to Knox Johnston’s or Moitessier’s, and in many ways, more so.

And we would like to think that our Galway would be the boat King would want to sail.

She would be reasonably light at 9 tons, compared to today’s Joshua’s 15! She’ll have a sweet, long waterline length pretty darn close to her overall length of 40 feet, compared to Joshua’s 33 feet-plus. Galway III would touch speeds of 11 or so knots and flash made-good times 50 percent better than Joshua’s. That’s 100 days less on the course. And 100 days less food, water, and fuel you need to purchase and, then, lug around the world.

Let’s not forget, Moitessier famously began throwing things over the side, like valuable wire and wine, mid voyage to lighten his Joshua’s load. What would this sailing genius have given to travel with 100 days’ less stuff!

A most expensive slow boat.

But Joshua is still the affordable option? Today’s version is cheap, right? Yes, according to the race website, the modern Joshua is a whole lot of boat for the advertised 300,000 Euro price tag. If you’ve been following our discourse on boat pricing, you’re probably crunching the numbers already: 300,000 Euro is about $330,000. Divide that by 33,000 pounds, you get an amazingly cheap $10 per pound. We will tell you, frankly, you will be very fortunate indeed to build the boat for anywhere near that price.

But our Galway III is 60 percent the weight of Joshua. And she should be, in theory, that exact proportion cheaper to build. That’s not to say we are offering a sub-$200,000 boat here. We are not up to speed on Joshua’s exact construction and cost schedule. But it is fair to say that today’s Joshua one-design forces racers to pay a penalty to go back in time. A trip that will stick these poor racers with a lump of a double-ender man-killer, that’ll guarantee you spend a year of your life soaking wet and going slow around the world.

If Moitessier’s Joshua deserves its moment in the retro sun, by all means, give it one. Go buy one that’s out there, restore it and race it in the next race. But for a new build, it’s simply off-message for this marvelous event to fail to seize the opportunity to invest money in a boat one can keep — and enjoy — for the rest of one’s life!

Remember, Moitessier gave away his beloved Joshua — for $20, so the legend says — when he realized she was too much for him to handle.

Let’s learn from the master, shall we?