Understanding the Evolution of Headsails

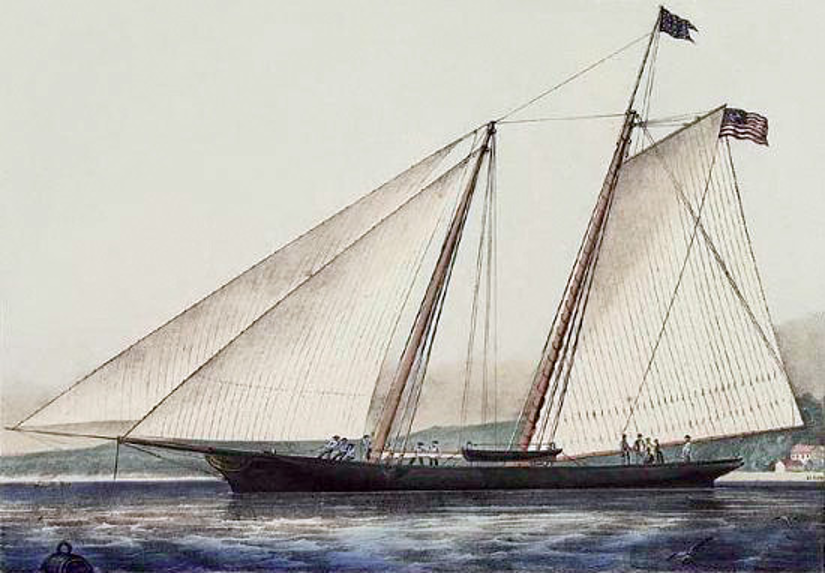

Over the years, we’ve seen a lot of evolution of sailboat rigs. Early yachts, like the schooner AMERICA (for whom the Cup was named), were among the first vessels to adopt the then-radical notion of abandoning square sails in favor of sails that could point somewhere close to upwind. However limitations in manual strength and the materials used in sails and rigging made it impossible for sails to be large, strong, and shapely all at the same time, so sail plans were divided into small sections with many sails. AMERICA had two mainsails (actually a mainsail and a foresail) and two jibs in the foretriangle.

Sailors being a conservative lot, evolution happened about as fast as continents drift. Even as rigging changed from hemp to stainless steel, and sail cloth changed from flax to cotton to Dacron, sail plans remained largely the same. By the 1960s most racing boats had discovered that a single mainsail worked better than two: yawls and ketches were abandoned in favor of higher-pointing sloops and cutters. But foretriangles remained split, especially aboard non-racing yachts without the luxury of plentiful and athletic crews: the manual strength limitation still dictated that a single big jib was too big for safe and efficient handling when individual sails had to be dragged to the deck and subdued, so most foretriangles were divided into jib and staysail, especially for shorthanded sailing or offshore work.

Nowadays, with modern dependable roller-furling, virtually every sailboat is a Marconi sloop with a single jib. But on the fringes, both out front in innovation and lagging behind in the tangles of tradition, we see variations on the theme. Let’s explore how each sail plan works and what their strengths and weaknesses are, roughly in chronological order.

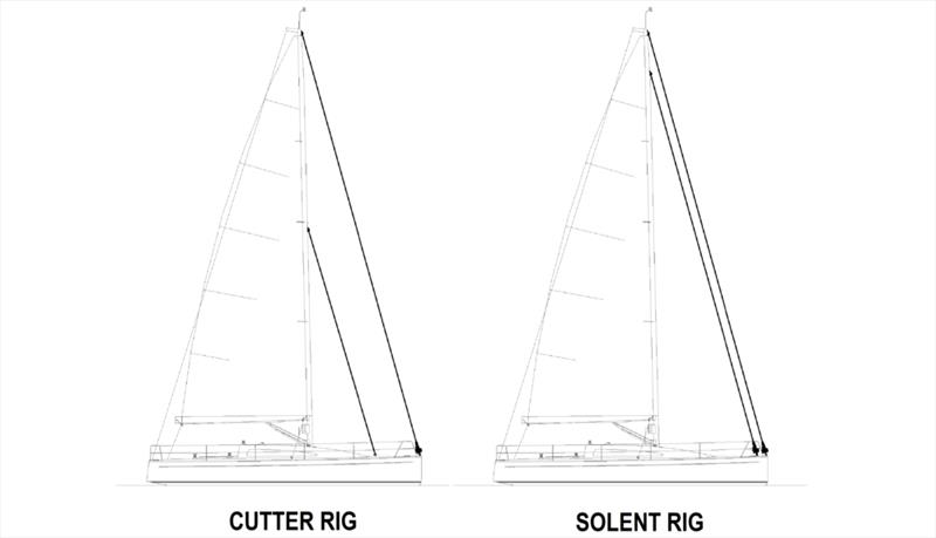

The Cutter:

The standard long-distance cruising rig of the second half of the 20th century. An outer forestay, usually to the masthead (and often landing on a short bowsprit), and an inner forestay about 2/3s of the way up the mast and out the foredeck. The outer jib is often a “yankee” cut—high-clewed with sheet passing outboard of the main shrouds and sheeting to the rail, with the inner sail – the “forestaysail” or simply “staysail”—sheeted to the cabin top, or to the end of a self-tacking boom.

Advantages: For a hundred years, this rig has been touted by “rust-your-eyeballs-out” salts as sturdy, versatile, and easy to handle—and it is, in many ways.

- The inner stay stabilizes the mast against pumping and provides a safety factor if the outer stay should break.

- Redundancy in two headsails

- The smaller staysail can be an excellent storm sail

- The yankee is well-shaped for efficiency when reaching… but:

Disadvantages:

- Yankee and staysail add up to about the same area as a standard working jib, but because they need to work together, and the wind across each sail influences the other, they’re much harder to trim for effective windward work.

- There are two sheets to handle every time you come about (not true if the staysail is on a self-tacking boom—but then there’s a self-tacking boom cluttering your foredeck).

- The Yankee loses upwind efficiency compared to a lower-cut working jib, where the deck provides an end-plate effect to keep high-pressure air from slipping around to the low-pressure side.

- The wider sheeting angle of the Yankee equates to a less efficient tacking angle.

- To enjoy the added structural support of the mast, the inner stay should be opposed by running backstays, further complicating deck equipment and tacking duties.

Sloop with Overlapping Genoa:

From around 1970 to the 2000s, this was the standard rig for 90 percent of inshore racers and cruisers, usually with forestay to the masthead rather than a fractional rig. Racing boats carried genoas with 150% (to as much as 180%!) overlap, wrapping outside shrouds, which were commonly set inboard on heavily loaded structural bulkheads to allow closer sheeting angles. In the interest of easier handling, cruisers made do with a mere “135”, or 35% overlap.

Advantages:

- The overlap in the genoa was less heavily rated in 20th-century rating rules, so the extra sail area contributed more to boat speed than it cost in rating.

- The “slot” effect sped up the wind across the leeward side of the mainsail, too, so main and genoa worked together as a single foil. In extreme racing examples, the mainsail got so small and tall that it was little more than vestigial, and the lion’s share of driving force came from the huge genoa.

Disadvantages: one huge one:

- Overlapping sails are a PAIN to tack. Because racing was setting the style of production boats, cruisers were saddled with a very un-handy rig that wasn’t big enough for good sailing in lighter breezes without using an overlapping sail, so they suffered with mediocre performance and a slightly smaller pain to tack, with a “135”.

Several smaller ones:

- Inboard shroud placement puts much higher loads on both boat and rig than if shrouds are out near the rail. Loads are concentrated on a single bulkhead, too, instead of being spread along the most structural part of the boat, the hull skin itself.

- Big genoas are hard to roughhouse to the deck and then to flake (although as roller-furlers became more reliable this became moot).

- In heavy breeze the only meaningful way to shorten sail is to change to a smaller jib, since the mainsail is such a small portion of total sail area. Or partially furl it on the headfoil and live with a very poor sail shape and a loaded sail where it’s not designed to be.

Modern Sloop

In the 1990s, rating rules evolved to do a better job of fairly rating sail area, and the rating advantage of the overlapping sail disappeared. This was welcomed by racing sailors, who immediately embraced the idea of designing rigs that performed well with smaller jibs and bigger mains. Sailors still being a conservative lot, cruisers stuck with their challenging to manage overlapping genoas and mediocre performance for several more years before the advances began to trickle down. Modern Sloops feature forestays a modest distance below the masthead for a fractional sail plan with the “fraction” not much below 1.

Advantages:

- Stephens Waring really likes this rig, and most of our boats, which have been designed since 2000, employ some variation on this theme.

- A smaller jib that doesn’t overlap the shrouds makes it easier to track and trim. Upwind sheet positions closer to CL allow tighter tacking angles, so tacks are faster, using less crew for faster maneuvers when racing and less fatigue when cruising.

- Your choice of headsail is not a make-or-break decision—in fact, many less-race-oriented boats (like our own boat ZINGARA) have only one jib, used in all winds from 5 to 35 knots. If you’re a passionate racer, your sailmaker will happily sell you several jibs for different wind ranges, but they’ll all have the same basic dimensions—the difference will be in sectional shape and materials, not in the sail area.

- Shrouds at the rail mean the mast and boat experience smaller loads, so the mast and rigging can be lighter and smaller in section for more stability and aerodynamic efficiency.

- The rig is designed with the appropriate sail area for operating in lighter winds, so you are not relying on the added sail area of the overlap to deliver performance in light air. Conversely, when the wind strengthens, you’re not saddled with changing headsails to reduce sail; instead, you tuck a reef into the mainsail and continue with a well-balanced rig and your original jib.

Zingara with newly refit Modern Sloop Square-top Rig designed by Stephens Waring. Photo Credit: Alison Langley. - If you have a fractional rig, either a forestay set inboard of the stemhead, or a short sprit/anchor roller, you can set your spinnaker to the masthead and stemhead, and keep it clear of the jib. You can even supplement your ”upwind” inventory easily for VERY light air and for close reaching by adding a “tweener” reaching sail on a roller and soft stay to the masthead. These are quite nice for cruising but less useful for racing, where their window of effectiveness is pretty narrow and they tend to increase rating.

Disadvantages:

- Honestly, it’s hard to come up with any. The taller, narrower jib is not the best shape when cracked off for reaching—but the bigger mainsail offsets this limitation, and a 150% genoa isn’t a great reaching sail either.

Solent Rig

Developed on superyachts in the 1990’s, the Solent features two permanent stays, quite close together: an outer one to masthead and stemhead, and an inner one a foot or two inside the outer. The inner one flies a “Solent” jib—a 100% blade named for the often-windy Solent strait between the South Coast of England and the Isle of Wight—to be used for breezy upwind work, and the outer one has a larger overlapping genoa or reaching sail for lighter air. Because the stays are so close together, the rig relies on modern roller-furling for effectiveness. In recent years the rig is often fitted with a deeper, lighter sail on the outer stay, more suited for reaching than true upwind.

- Shifting gears is nearly effortless, with two sails ready for use at the pull of a line (or push of a button). Breeze drops? Roll up the blade and deploy the large genoa. Sea breeze builds? Reverse the process.

Disadvantages:

- Windage: the unused rolled sail is a lot of drag to keep up in the foretriangle—particularly if it’s the outer one, making a large-diameter wind-break at the leading edge of the blade jib.

- Tacking: with so little space between the stays, the outer sail MUST be furled with every tack—slow, and relies on using the furler frequently.

- Weight aloft: two furlers, stays, and sails are twice as much weight up high as one.

- Expense: again, two is more than one.

- The complexity of tuning: with two permanent forestays so close together, keeping proper tension on each is challenging. With recent innovation in modern sail design of the “structured luff”, where the load to support the sail’s leading edge is handled not by a stay but by the fibers in the sail itself, the tuning issue is greatly mitigated—the inner stay becomes the only structural stay. It can be tuned properly, and the outer sail is supported by its own structure rather than a metal stay and furler foil.

Variation: the ultimate evolution of the Solent concept is seen in single-handed offshore racing boats like the Open 60’s, where three or as many as four headsails may be set most or all the time on their own furlers, and “sail changes” in the traditional sense are very rare indeed. Shifting from offwind reaching in the light, to three-reef beating in 35 knots, happens by rolling and unrolling the appropriate headsails, not by lowering sails to the deck and stowing them. Yes, the windage and weight obstacles still exist—but in these fast race boats, the limiting factor is the strength and stamina of the crew, and quick and efficient gear changes that keep the crew rested are a more effective way to achie high performance. Family cruisers would do well to study the innovations these boats and teams have developed.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the choice of foretriangle design comes down to personal preference. For some traditionalists, the solidity, redundancy, and versatility of an old-school cutter win over more efficient rigs. For others, embracing the ability to shift gears from light winds to heavy lobbies for the Solent.

In our decades of yacht design, we’ve designed boats with all of the above sail plans. We’ve even hybridized between them: fitting a removable inner forestay inside a modern fractional rig is a great way to add versatility for heavy-weather sailing offshore, where the working jib can stay rolled on its foil and a smaller heavy-weather jib or storm jib can be set on its own inner stay. That jib can even be set up with a “structured luff” and soft stay or torque rope on a furler.

When we design foretriangles, we look at a few elements in descending order of importance: Performance (it’s fun to sail fast); efficiency (ease of handling is key to enjoying the sport); and versatility (being able to meet every anticipated condition with confidence). The balance of these elements varies for each project and each mission brief. Working with our clients to find the perfect balance for their sailing style is a welcomed challenge and keeps us busy innovating in pursuit of the ideal sail solutions.

Ready to Rethink Your Sail Rig? Connect with SWD.

207-338-6636

Other Great Reads:

https://stephenswaring.com/sailing-back-to-zingaras-roots/

https://stephenswaring.com/marine-engineering-for-ups-why-my-keel-does-not-fall-off/

https://stephenswaring.com/how-to-launch-a-torqeedo/